A Deep Dive Into The CIA’s Guide On How To Sabotage Fascism Starting In The Workplace

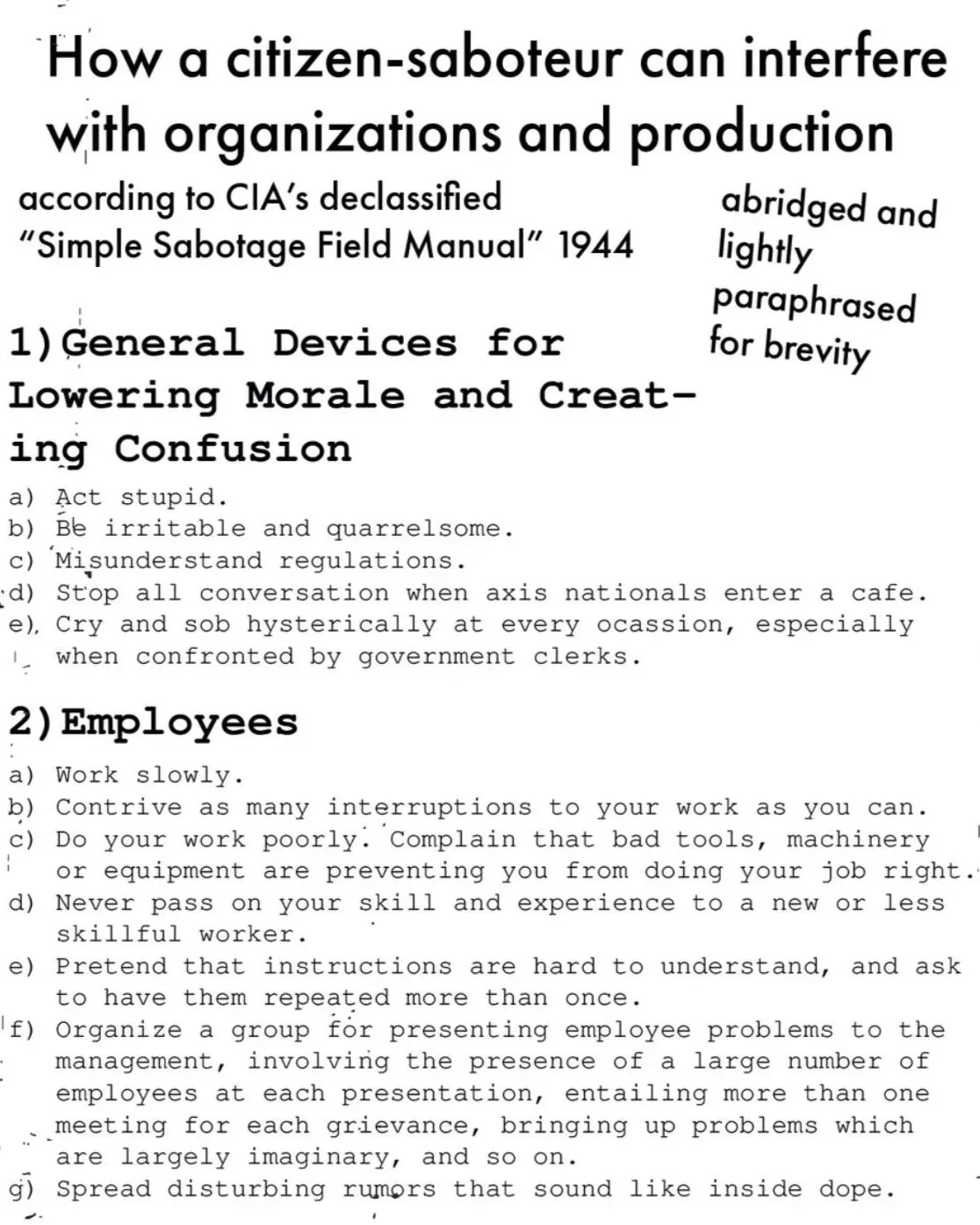

Source: The CIA. Steps 1 - 2.

The OSS’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual (1944): Why a WWII Pamphlet Still Makes People Nod — and Nervous

In January 1944, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) — the U.S. wartime intelligence service and eventual precursor to the CIA — produced a short, tightly written pamphlet called the “Simple Sabotage Field Manual.” It was designed as a low-tech, widely distributable guide for civilians in occupied countries to weaken an enemy’s war effort through small, dispersed acts of disruption.

The manual’s tone and focus are pragmatic: the goal was not dramatic explosions but multiplying tiny failures so industrial output, transport, and administration slowed and frayed.

The manual was created in the context of total war. OSS planners wanted tools that ordinary people — with no special training or weapons — could use to resist occupation or otherwise hamper an adversary’s ability to coordinate and produce.

Rather than elaborate sabotage of railroads or factories by trained agents, the pamphlet emphasized widespread, small-scale actions whose cumulative effect would be to sap productivity and morale. It was intended for use by local “citizen-saboteurs” and for OSS training.

Image generated with AI

What the manual emphasizes (high level)

Fascism can take many forms. Third-party organizations and businesses—law firms, government departments, universities, and the like—may find themselves compelled to engage with an authoritarian regime or government whether domestically or abroad. In those situations, institutions have tools at their disposal to slow or blunt the regime’s momentum. This piece is an abridged summary of themes from a historical CIA manual on undermining authoritarian influence in business and civic partnerships, focused on nonviolent, lawful strategies for resistance rather than operational tactics.

Obviously, because this guide is meant strictly for businesses and companies that are compelled to engage with an authoritarian regime, these strategies are not meant to be taken seriously during peacetime or at a company with no compelled relationship with an authoritarian or fascist regime. For example, a vineyard in Nazi occupied France wouldn’t implement these tactics to ruin their wine production, whereas it might make more sense to implement these tactics at a textile mill that produces uniforms for soldiers.

Rather than detailing violent or technical sabotage, the manual focuses on making organizations and systems less efficient — through friction, confusion, incompetence, and delay. Its central insight is organizational: large bureaucracies rely on predictable routines, clear chains of command, and motivated workers; if those break down, the system performs poorly. The manual therefore reads at times like a cheeky handbook about how to be inefficient on purpose, framed as wartime strategy.

Source: The CIA. Steps 3 - 4.

Declassification and cultural afterlife

The pamphlet remained classified for decades and was declassified in the 2000s. Since then, it has enjoyed periodic resurgences in popular culture and management circles — often shared as a curiosity or a cautionary text. Modern readers treat it in multiple ways: as a historical relic of guerrilla resistance tactics; as a tongue-in-cheek guide that exposes how fragile institutions can be; and, sometimes, as a misapplied how-to for passive-aggressive workplace behavior. The CIA’s own release of the document and subsequent commentary helped spark renewed interest.

There are a few reasons the manual resonates now:

It’s an organizational mirror. The manual’s “do less, break processes, sow confusion” logic reveals the same fault lines corporate and bureaucratic systems have today. That’s why managers and organizational scholars sometimes cite it when discussing failure modes.

It’s a pop-culture Rorschach test. People project onto the pamphlet: activists see a tool for resistance, disgruntled workers see validation for frustration, and critics warn about its potential to inspire harmful acts.

It prompts an ethical conversation. The manual forces a question: when (if ever) is sabotage justified, and where’s the line between civil resistance and criminal harm? Reading it now obliges us to weigh motives, targets, and consequences rather than glamorize disruption.

A historian’s caveat (and a legal/ethical one)

It’s worth stressing two things. First, the manual is a historical document tied to a specific wartime context — it was intended as an instrument of Allied resistance against occupying armies, not as a pop management tool. Second, many of the actions it suggests would be illegal or dangerous in peacetime; treating the pamphlet as a literal how-to for modern sabotage is irresponsible and, in many cases, unlawful. For those curious about the manual’s content, reliable declassified copies are available from government archives and libraries; scholarship about the manual is a safer way to engage with its lessons than attempting to emulate its tactics.

The Simple Sabotage Field Manual survives in collective memory because it sits at the intersection of intelligence history, organizational critique, and cultural folklore. It’s a compact demonstration that large systems — even those designed for war — can be undone by small, repeated failures. That’s an uncomfortable insight, and the document is useful mostly as a prompt for reflection: on how societies organize work, how resistance is framed in wartime, and how we should responsibly interpret historical texts that flirt with disruption.